What do a perfectly sculpted ancient athlete, a graffiti mocking early Christian devotion, and the austere robe of an Orthodox monk have in common?

The answer is that Greece is Metal. Welcome to a journey into the aesthetic metamorphosis of Greek cultural and religious expression. From the gleaming muscularity of the Apoxyomenos to the black-robed stillness of the megaloskēmos, this evolution tells a story not only of art but also of the sacred, the political, and the philosophical.

Apoxyomenos: Bronze, Oil, and Beauty

Let us begin with the Apoxyomenos with a bronze statue dated to the 2nd century BCE, pulled from the Adriatic Sea near Croatia and painstakingly restored. This figure depicts a young athlete scraping oil and dust from his skin with a strigil, a practice deeply ingrained in Greek gymnasium culture.

This image of physical perfection symbolizes classical Greek ideals: balance, bodily harmony, and youth in its prime. The Apoxyomenos was not merely an artwork, no, it was a shrine to beauty, a medium through which the sacred could be glimpsed.

Ancient Greek athletes competed in the nude, their bodies oiled and dusted, embodying ideals of strength and discipline that bordered on the divine. These aesthetics, often homoerotic in tone, were seen as expressions of kalokagathia which is the unity of physical and moral excellence.

From Riace to Ruins: Pagan Decadence?

The Riace Bronzes, two warriors dated to the 5th century BCE, serve as a powerful counterpart to the Apoxyomenos. Their intense realism, curly beards, and exaggerated musculature convey a sense of gravitas, even aggression. These figures, perhaps once placed in temples or public spaces, were more than decorative, they were spiritual emissaries.

Yet, by the early Roman Empire, some argue that paganism had begun to over-ritualize itself. Gods multiplied endlessly, cults grew obscure, and what once felt sacred began to feel cluttered. As Rome expanded, it absorbed Egyptian, Persian, and Anatolian deities into its pantheon. Everything had a god, everything, from the hearth to the cup of wine. What began as a symbolic system of cosmic harmony morphed into spiritual saturation.

Alexamenos: Graffiti and the Rise of Christianity

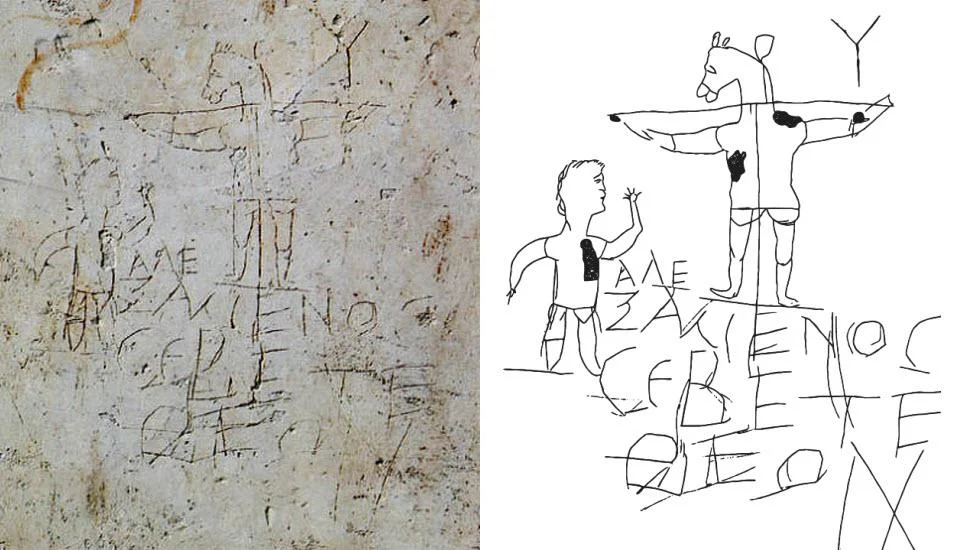

Enter Christianity, with its radically different vision of the sacred. One of the earliest surviving images of Christian iconography is the Alexamenos Graffito, carved on a Roman wall around the 1st or 2nd century CE. It depicts a man worshipping a crucified figure with a donkey’s head which is an apparent satire of Christian belief.

But satire or not, this image reveals something powerful: the sacred had shifted. No longer was divinity found in the heroic, oiled youth. It now resided in suffering, humility, and asceticism. The monastic aesthetic that followed, especially within Eastern Orthodoxy, emphasized dark robes (megaloskēma), blind faith, and withdrawal from worldly beauty.

The anchorites, early Christian hermits who retreated to the desert or caves, embodied a stark rejection of the visible in favor of the invisible. In place of gleaming bronze, there was sackcloth. In place of athleticism, there was prayer.

From Apoxyomenos to Saint Paul

The turning point can be traced to figures like Saint Paul, who preached in Athens around the mid-1st century CE. He warned against idol worship on the Areopagus, right at the heart of classical culture. He asked Athenians to look beyond marble gods and sacred oils to something singular, transcendent, and invisible.

This shift from polytheism to monotheism also came with a profound change in artistic language. Christian art (especially in its early form) was less about realistic depictions and more about symbols, abstraction, and humility. The spiritual replaced the sensual.

Byron and the Return of the Romantic Sacred

Fast forward to the 19th century, and we see another key figure, Lord Byron, a Romantic poet who inscribed his name on Cape Sounion. Byron’s reverence for ancient Greece wasn’t purely nostalgic; it was revolutionary. He saw in ancient Greek ruins the lost sacred beauty worth dying for.

In a sense, Byron closes the circle. By tattooing his name into a classical ruin, he participates in the same aesthetic longing that once produced the Apoxyomenos. He helped awaken a modern sense of the sacred that includes both the pagan hero and the Christian martyr.

Conclusion: What is Metal?

So, is Greece metal? >> Absolutely.

Not just because of its warriors and ruins but because of its raw aesthetic honesty & its ability to oscillate between divine flesh and spiritual asceticism. Greece is metal because it never forgets the tension between beauty and belief, between the body and the soul.

In Apoxyomenos, we find a yearning for the ideal form. In Alexamenos, a graffiti mocking the crucified god, we find the birth pangs of a new spirituality. In the megaloskēma, the black robes of monks, we see the perseverance of the sacred even when beauty fades.

Sources

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. The Art and Culture of Early Greece, 1100–480 B.C. Cornell University Press, 1985.

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Clark, Kenneth. The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton University Press, 1972.

- Freeman, Charles. A New History of Early Christianity. Yale University Press, 2009.

- “Apoxyomenos.” Croatian Apoxyomenos Museum.

- “Alexamenos Graffito.” Early Christian Art, Bible Odyssey.

- Saint Paul’s Areopagus Sermon. Acts 17:16–34.

- Riace Bronzes. Reggio Calabria National Archaeological Museum.